Architect Ethan Chan's Work Doesn't Need Your Attention.

But it'll reward you if you give it.

If you enjoy this piece, please consider sharing it or leaving a like or comment. Your support helps more people discover Gotta Start Somewhere on Substack. Thank you.

Architect Ethan Chan leads me and photographer Marien Wilkinson through Midtown Manhattan on a 90-degree day. I can feel sweat bleeding through my tank top, as an SUV honks and zips down Fifth Avenue behind us.

Ethan turns a corner into a shaded courtyard where the sound of rushing water replaces the city’s honking, ivy climbs the walls, lanky honey locust trees cast shadows, and the air shifts from stifling hot to cool.

“Yeah, this is one of the spaces in the city I like a lot,” he says.

Ethan’s connection to space and form began early. Without the drama of a struggle or reinvention narrative, which I am instinctively drawn to, his story is measured, focused, and calm like Paley Park.

“It sounds cliché now,” he says, “Or maybe diagnostic, but my parents say that when I was young, I would cry if the wall color in a room was too loud. There’s something about obsessing over your surroundings that seems to predispose you to design. Or maybe it’s just the desire to assert some agency over the space you’re in, to tune into the frequency of the world.”

Ethan knew going into undergrad at Rice University, one of the best undergraduate architecture programs in the country, that he wanted to study it. In his senior year at Rice, Harvard University accepted him into its graduate program. After just two years of practice, Cornell invited him to teach. And now he has his own studio, Studio Ethan Chan, which designs architecture, furniture, and jewelry, and another, Two Fifteen, with co-designer Pablo Castillo Luna.

As we spoke, I grew nervous. Where is the intrigue, climax, or denouement when someone’s story appears…easy…clean…perfect? I told him that, half joking, half fishing. “I’m going to title this article ‘Ethan Chan’s Life Has Been Perfect.’”

He laughed and said, “Of course, now I want to tell you everything that’s wrong with me.”

But I realized Ethan isn’t the character this story is about when he says, “Maybe this is going to sound very strange, but objects and spaces are like friends to me. They feel alive. It feels like it's you and me here, but the place is also participating as another character,” he says.

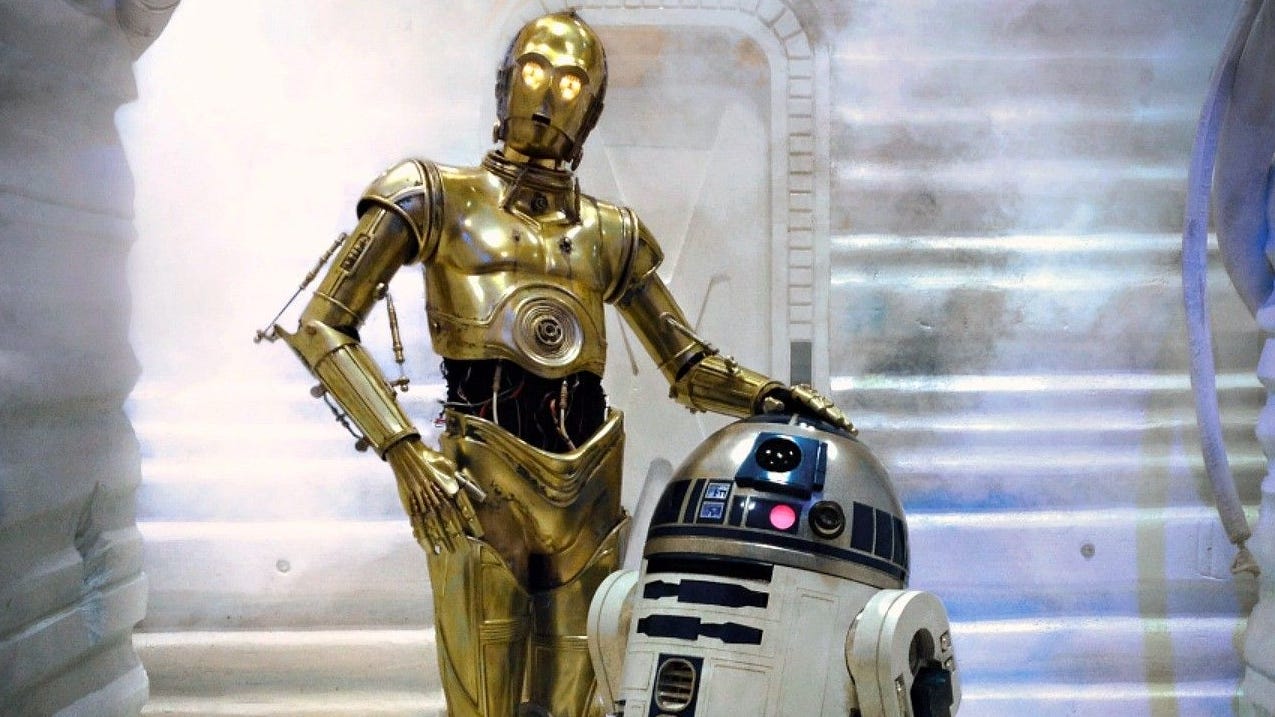

He explains how proportion and shape give objects their personalities. “Think about R2D2, short and stout, so maybe you associate him with loyalty, groundedness.”

“C3PO is tall, gold, and narrow—we project cerebral traits onto him. That’s how buildings work, too. Those physical associations form our emotional responses to them.”

Architects have always played with those emotional cues, oscillating between restraint and exuberance. The Classicists prized harmony and balance, building precise structures so that nothing could be added or removed without breaking the whole. Mannerism featured elongated forms, distorted proportions, and a playful, sometimes irrational, use of architectural elements.

“And then there are modern architects, like Daniel Libeskind. He’s famous for designing Holocaust museums that destabilize or disorient you. The architecture itself aligns you with the subject matter’s intensity.”

“But it’s all about context,” he says. “I like calm environments. I also appreciate noxious spaces, like carnivals or loud concerts.”

“So what, then, in your view, distinguishes a good architect?” I ask.

He answers without hesitation, “People ask me this all the time, and I’ve landed on three words: audacity, intensity, restraint.”

“Audacity, because you have to take a risk. You’re standing in an empty lot, imagining something that doesn’t exist yet.”

“Intensity, because the best buildings are obsessed over. You can feel it in the drawings.”

“And restraint, because not every idea needs to be chased. There are always clever flourishes that tempt you. But you have to say no to what doesn’t serve the core.”

“A building,” Ethan tells me, “Doesn’t just stand on its own; it lives in dialogue with its neighborhood, its people, and its history, especially in New York, where even a basic housing development enters a fraught landscape of redlining, disinvestment, and gentrification.

“Every structure is a statement,” he says, “It’s your task to make this place better for the people who already are or will soon be there.

“As Renzo Piano says, something like, ‘As an architect, at 10 AM, you need to be a poet, by 11 AM, an architect must become a humanist, and by noon, a builder’,” Ethan says.

“It sometimes feels like threading a needle. But there’s a responsibility. Responsibility to the users, community, client, and their financial interests. Responsibility to the environment.”

“Architecture, at its best, doesn’t shout. It shapes behavior, reflects values, and can either divide or connect. Oppress or uplift. You don’t have to notice it. But it’s always there, humming beneath the surface of life.

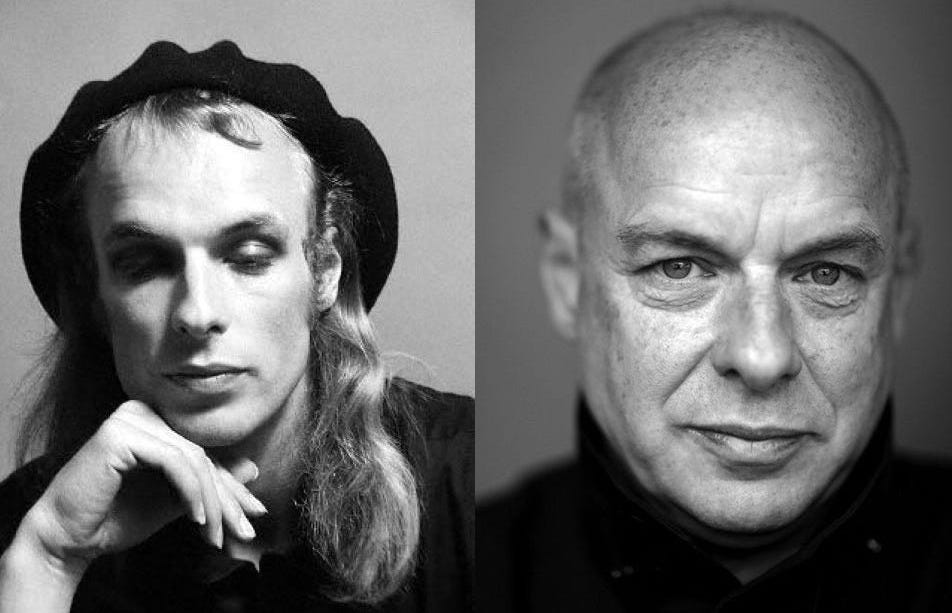

“It’s like the Brian Eno quote, ‘Equal parts interesting and ignorable.’ He was talking about ambient music—how it shouldn’t demand your attention, but reward it if you give it. That’s how I feel about buildings.”

“Minimalism, often mistaken for virtue, is actually about precision and cost,” he says and laughs. “Which then you can apply the Dolly Parton quote, ‘It costs a lot of money to look this cheap.’ It’s the same with architecture. It takes real thought and real expense to make something feel effortless.”

As Marien photographed Ethan sitting in the wire mesh chairs of Paley Park, I walked towards the smell of French fries, noticing a man standing within the park’s wall. The screen above him read, The Lunch Box, and displayed a menu of sandwich and salad platters.

“Look at these long lines on weekdays,” he says after I ask him what it’s like working within this park. “The location of this kiosk is great for business. We do really, really well here. Don’t you worry,” the owner of The Lunch Box assures me.

“Architecture at its best enables,” I remember Ethan telling me an hour earlier. “It sets the stage for real life to happen. For dinner with friends, for falling asleep under a window, for studying in the early morning light.”

Like Paley Park enabled The Lunch Box owner to make a living, and its patrons to enjoy a meal.

“Architecture foregrounds what the space desires, whether it’s people, connection, work, or even solitude. And that’s why I keep coming back to it, and I live inside it, mentally and physically,” Ethan says. “Because at the end of the day, architecture gives form to how we live, and, when it’s really good, it permits us to live better.”

Maybe the simplest place to start, if you gotta start somewhere, is by paying attention to what you’re drawn to and what unsettles you, about the spaces you live in each day.

Readers, if you enjoyed this piece, please consider sharing it or leaving a like or comment. Your support helps more people discover Gotta Start Somewhere on Substack. Thank you!

Thank you also to Ethan Chan for trusting me with this piece, and for being one of the people who studied next to me last summer when I wrote at The Bean in the East Village, determined to get this blog and my novel off the ground.

Beautifully written!

Awesome piece! I love thinking of architecture in this way, as something that plays a quiet role all the time.